Author | Lucía Burbano

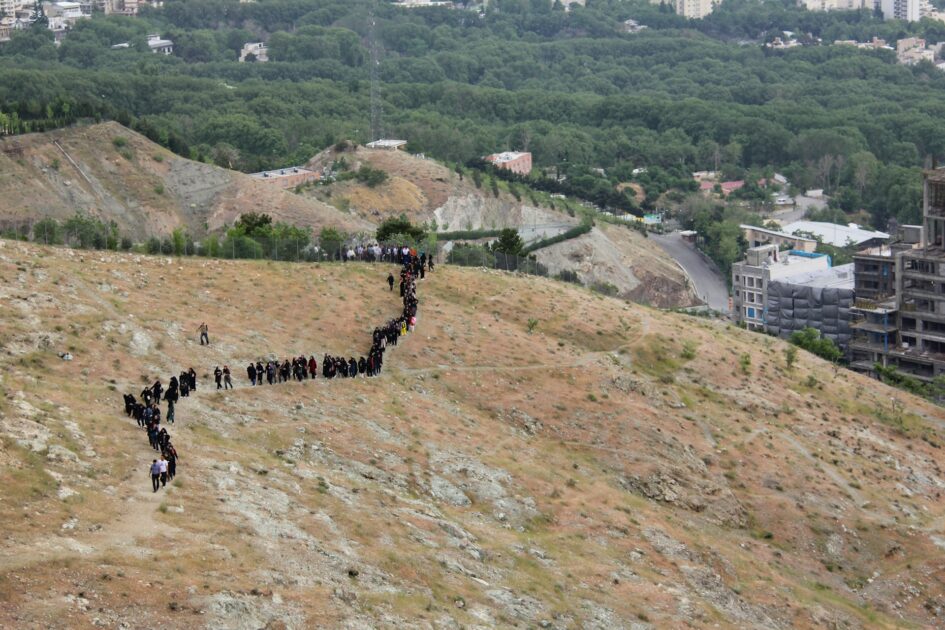

Iran is experiencing one of the worst droughts in the past 60 years, with rainfall at historically low levels and many of the main reservoirs and dams at critical levels. This situation is affecting water resources across the country, including Tehran, and has led authorities to warn of an unprecedented possibility in modern history: the need to evacuate the capital.

Given the situation, authorities have begun rationing water and have planned outages, including periodic supply interruptions in some areas of Tehran, due to declining reserves in key reservoirs such as the Amir Kabir and Latyan dams.

President Masoud Pezeshkian and other officials have publicly warned that if substantial rainfall does not occur for the rest of winter and supplies continue to dwindle, relocating the population of the capital, either fully or partially, could be considered.

Water reserves in Tehran at a minimum

Five reservoirs supply much of Tehran’s municipal water. According to figures from December 2025, the current reserves for each are:

- Amir Kabir (Karaj): 8% of its capacity

- Lar: between 5% and 7% of its capacity

- Latyan: between 15% and 20% of its capacity

- Mamloo: around 20% of its capacity

- Taleqan: comparatively higher but still low; between 50% and 53% of its capacity

These figures are closely tied to the limited rainfall in 2025 and early 2026. Last year, Tehran Province recorded only 2.2 mm of rain compared with the historical average of 55.9 mm, a decrease of 95%.

Why is it raining less in Iran and Tehran?

The rainfall deficit in Iran and Tehran in 2025 and early 2026 is multifactorial. It reflects a convergence of weather variability, large-scale climate dynamics, and long-term regional climate change.

Key factors include:

Persistent high-pressure block over the Middle East

One of the most immediate meteorological explanations is the dominance of stable high-pressure systems over Iran. This phenomenon prevents cloud formation, diverts storm tracks northward, and reduces the number of frontal systems reaching the Iranian plateau.

Shift of storm tracks from the Mediterranean

Iran’s winter rainfall depends largely on western storm systems originating in the Mediterranean. In dry years, these tracks shift toward Turkey and the Caucasus and weaken before reaching central Iran.

Climate change

Even when it rains, global warming disrupts the hydrological balance, as higher temperatures increase evaporation from soil and reservoirs, and precipitation falls as rain rather than snow in the mountains, reducing water storage in summer.

Soil degradation

Soil changes caused by human activity, such as deforestation in watersheds, can worsen the effects of drought. They erode the soil, accelerate desertification, and lead to the loss of wetlands.

Water patterns have changed

Iran is experiencing increasingly extreme rainfall, causing flash floods instead of steady rain that would replenish reservoirs.

What measures is Tehran taking to fight the drought?

Iran, and Tehran in particular, are implementing a series of measures to address the current drought.

- Periodic cuts and rationing in Tehran:

Authorities have introduced planned water supply cuts, such as reduced nighttime pressure or temporary outages to prevent waste. These measures aim to lower consumption in a city that uses around 3 million m³ per day.

- Infrastructure and emergency supply projects:

Tehran has accelerated the implementation of projects such as new circular pipelines designed to redistribute water more efficiently.

- Cloud seeding and weather intervention

Authorities have launched programs to artificially induce rainfall in areas affected by the drought. This is a widely used emergency solution in arid regions, but it usually only produces a moderate increase in precipitation if conditions are favorable.

- Specific restrictions and supply controls

Authorities have banned or restricted certain uses, such as supplying public and private swimming pools, to prioritize essential consumption.

- Long-term adaptation

Experts note that agriculture uses around 90% of Iran’s water and that more efficient irrigation and crops are necessary. However, this requires a deep structural reform, which is still under discussion.

The FAO and the Iranian government have launched technical cooperation projects aimed at strengthening climate-resilient agriculture and adaptive water management in key regions.

- Strategic decisions

President Pezeshkian has raised the idea of relocating the capital to a region with less water stress, although this decision is complex and controversial.

Importing water from neighboring countries such as Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan is also not ruled out as part of a broader response to the crisis, though no details have been disclosed.

Is the evacuation of Tehran a real risk?

Tehran has around 10 million residents, so relocating even a small portion of the population would be extremely complex, both politically and operationally.

Given current conditions, the most feasible approach is implementing partial measures like those already in place. However, if restrictions fail and the drought intensifies, Tehran’s long-term viability could become a strategic challenge with no international precedent.

Several scenarios consider localized displacement or partial relocation of Tehran’s residents if the drought and low water storage continue for two more years.

In this context, measures under consideration include moving government offices, restricting residency permits, or significantly downsizing urban areas, rather than a total evacuation.

Photographs | Unsplash/ hosein charbaghi, Unplash/Alireza Akhlaghi, Unsplash/Oleksandr Sushko, Collabmedia/istock, CanY71/iStock