Authors | M. Martínez Euklidiadas, Raquel C. Pico

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (Spain) is renowned for its innovative architecture and the beauty of its designs. To such an extent that it has served as inspiration for architects across the world and it has been used in countless science fiction movies, helping to make it one of the iconic buildings of recent decades. Its futuristic forms —a design by Frank Gehry that has established it as one of the most prominent examples of postmodern architecture in Spain— is not the only relevant aspect of the building that put the city in which it is located on the map and served as the driving force behind an urban regeneration process. Here are 9 reasons why it deserves its global recognition.

Why is the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao famous?

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao has won over 70 international awards for so many different aspects than one may imagine. Although many of them are related to its design, the way in which it was built or the way it operates on a daily basis, it has also won awards for best website, Mérito a las Bellas Artes (Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts) award, an award for lighting, global accessibility, CSR, Women’s Empowerment or web accessibility among many others.

Some amazing facts about the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

Below are a few of the most interesting, yet little known facts about the museum. These include:

A dozen Guggenheim museums

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao has numerous older siblings, equally iconic buildings in their own right: the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1959) in New York and the Guggenheim Museum in Venice (1979). The name was given to it by the Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation, which set the standard for what to expect with the pioneering Guggenheim in New York. This museum combined the art of its content with the art of its form, as its iconic building itself is a piece of contemporary art.

There were also numerous Guggenheim museums in Berlin between 1997 to 2012 and in Las Vegas between 2001 and 2008, which were closed by the foundation and there were various attempts to open museums in Guadalajara (Mexico), Vilna (Italy) and in Helsinki (Finland), that never materialized.

The Guggenheim Foundation is currently pursuing two other art projects: a new museum and an expansion. Frank Gehry is the architect behind the future Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, which will be “an experiment in inventive 21st-century museum design” and will use sustainable elements. For now, it is still under construction with no official opening date.

Adding to this is the proposed expansion of the Guggenheim Bilbao, which will be located in the Urdaibai area and which the museum promises will be a sustainable architectural project respectful of nature. Environmental organizations, such as Greenpeace, have criticized the plan, however, noting that the museum will be installed “in the heart of the Urdaibai Biosphere Reserve,” a critical area due to its ecosystem value.

Over 25,000 m^2 of titanium

The shell that covers the museum, and which has become one of the most recognizable elements of this piece of contemporary art, is made up of around 33,000 thin titanium sheets which, according to the museum organizers, “provides a rough and organic effect, adding to the material’s color changes depending on the weather and light conditions”.

According to Juan Ramón Pérez, Site Manager of the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, “titanium was chosen because of its marvelous resistance to corrosion, durability, solidity and its incredible range of tones depending on the intensity and reflection of the light, which allows its color to change from dawn to dusk”.

There is no doubt that the choice of color and shapes were ideal for the presentation of the building, which changes the visual aspect of the building as the day goes by.

Farewell to the old industrial zone

Bilbao is an example of a city that found the way to renew itself in time —unlike previous industrial cities like Manchester or Detroit that failed to have that vision, and which took around twenty more years to do so— and the Guggenheim was key for this. The area in which the building designed by Frank Gehry was erected was an old industrial site that was rapidly declining, and which found the way to re-emerge as a cultural hub. The previously devalued area has made Bilbao a global leader in culture.

Rock climbers for cleaning

The facades of the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao are irregular and, therefore, they cannot be cleaned using conventional cleaning hoists. Instead, a team of professional rock climbers are in charge of brightening up the building every now and again and keeping this unique piece of architecture pristine.

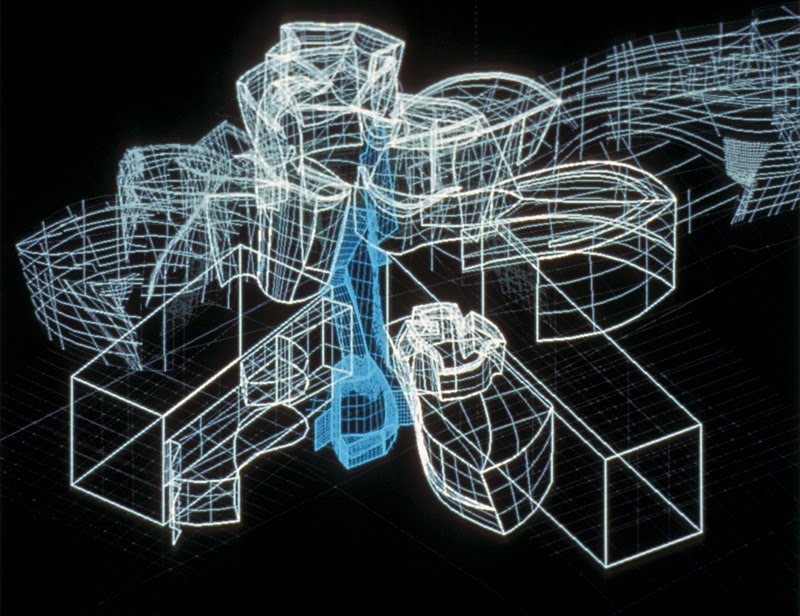

A computer-aided design ahead of its time

Today it is common, if not universal, for all public building designs to be created using BIM software. However, when the building was designed at the beginning of the 1990s, digitalizing the structure and using CATIA was unheard of. This program had been used in the French aeronautical industry, and it was the best software of its time.

A unique skeleton in its class

The previous image illustrates the technical complexity of building the Guggenheim, a museum in which not a single facade is the same as another. The truth is that it took not only the use of software that was ahead of its time, but also technicians who discovered new ways of working with apparently common elements such as steel profiles. The same applies to these, no two sections are the same, which posed a technical challenge.

Puppy, the flower-covered mascot

Puppy is a 12-meter-tall dog covered with thousands of real flowers. A team of gardeners is responsible for looking after it and decorating it according to each season. A complex system of nutrients feeds the flowers from inside. Puppy is the second creation of its kind by Jeff Koon. The original Puppy is in New York.

A first-class lighting system

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is a contemporary art museum and, at the same time, art itself. Its works of art are objects requiring exceptional lighting. Although this is an aspect of vital importance for all museums around the world, the Guggenheim gives it utmost priority. In fact, it has received numerous international awards thanks to its interior lighting.

A small maintenance army

Around fifty maintenance and cleaning technicians work in the Guggenheim in Bilbao on a daily basis, ensuring that nothing fails in this essential piece of postmodern architecture. Without them, the system would simply not be able to operate. “There are 7,500 light points and over 2,000 power sockets”, according to Óscar Rábade Romero, Head of Cleaning and Maintenance in the museum, “which means there are probably 5,000 m^2^ of technical rooms and corridors”.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao is a fascinating machine, and it is absolutely understandable why other countries have tried to copy its design. As with Puppy, it not only guards the art within, but rather it cannot help but form part of the global gallery.

The Guggenheim effect: urban regeneration through culture

Beyond the museum itself and its inclusion on the global list of iconic buildings, this piece of postmodern architecture is also the central figure in what is known as the “Guggenheim Effect” or the “Bilbao Effect”. In a way, as with other iconic buildings such as the Villa Savoye, the museum served as an architectural catalyst, one that set a benchmark.

The museum’s success story tends to overshadow the fact that, at the time, it was also surrounded by controversy. It opened in 1997, after a decade of work. During those years, the Nervión River basin—where this iconic building is located—had undergone an industrial restructuring process that had led to unemployment, disillusionment, and severe environmental degradation. At the same time, the final decades of the 20th century were a complex period in the history of the Basque Country: ETA was active, and terrorist activity was frequent.

The situation in Bilbao was less than favorable. The city’s image was that of a cold, rainy, unattractive, and not particularly pleasant place. All of that changed, and contemporary art became (alongside other changes in the broader context) a form of soft power. “The Guggenheim Bilbao is the greatest example in the last 50 years of how art can revitalize a city, combining political action, imagination, and the world offered by artists, with flawless execution,” Richard Armstrong, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and the New York museum, told the El País newspaper on the museum’s 25th anniversary.

When the museum celebrated its 25th anniversary, it was estimated that from its opening until the end of 2021, the Guggenheim had generated €6.5 billion in direct spending in the region. Tourism has also taken off across the area. The museum alone welcomed 1.3 million visitors in 2024, 67% of whom were from abroad. By comparison, visitor statistics for Bilbao in 1996 recorded 265,832 tourists.

Imitating the Bilbao Effect

The museum’s success and the impact of Frank Gehry’s building in creating a city brand, also led many other Spanish cities to invest in iconic buildings as attraction magnets (from the Cidade da Cultura in Santiago de Compostela to the Óscar Niemeyer Center in Avilés, and even the steel forest in Cuenca). Seeing Bilbao succeed, and noting that other cities had used their iconic buildings as a draw, like Les Espaces d’Abraxas, these cities were convinced they could achieve urban regeneration and a surge in tourism through unique architecture.

Most of these proposals (though not all) failed to replicate this success because they focused on the most superficial aspect (investing in iconic buildings) while overlooking the most essential elements, such as giving the facilities meaningful content or creating a “wow” effect similar to that of the Guggenheim Bilbao. The collapse of the real estate bubble during the 2008 financial crisis was also a turning point for these projects attempting to emulate the Bilbao Effect, as it drastically reduced, or in some cases completely eliminated, the funds needed to complete them.

Images | Mikel Arrazola, Jorge Fernández Salas, Jose María Ligero Loarte, Dorien Monnens, David Vives