Author | Arantxa HerranzAlthough it is hard to measure or monitor the exact population living in shanty towns, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) calculates that approximately 11.4 million people (6% of the country’s population) live in one of the 6,329 favelas or slums, distributed across Brazil.The state of São Paulo is the richest in Brazil. The city is the economic and financial centre, but also the city in Latin America with the highest number of people living in shanty towns. NASA, using photographs taken with it satellites, illustrated the growth of this large city. The most notable change that can be observed from NASA’s photographs is the spread of the suburbs, where growth has been fastest. Over the last decade, the inhabitants living in shanty towns in São Paulo reached 1.7 million compared with the 800,000 living in the city centre during the same period.

The growth of favelas

Much of the suburban growth took place in favelas, which emerged when people built their homes on the steep hillsides in areas that were unoccupied as they were deemed inappropriate for construction. An estimated 20 to 30 per cent of São Paulo’s population lives in favelas, which poses a challenge for the municipal government because these unplanned communities often lack connections to the basic sewage, water and electricity services.Paraisópolis is one of the largest recognised favelas in Brazil. It is one of the most graphic examples of how poverty and the most extreme wealth can be separated by just a couple of streets. Around 20,000 people live in the approximately 331 square kilometres it covers. But Paraisópolis is also an example of how the situation and quality of life its inhabitants can be transformed and improved.

The marginalisation problem

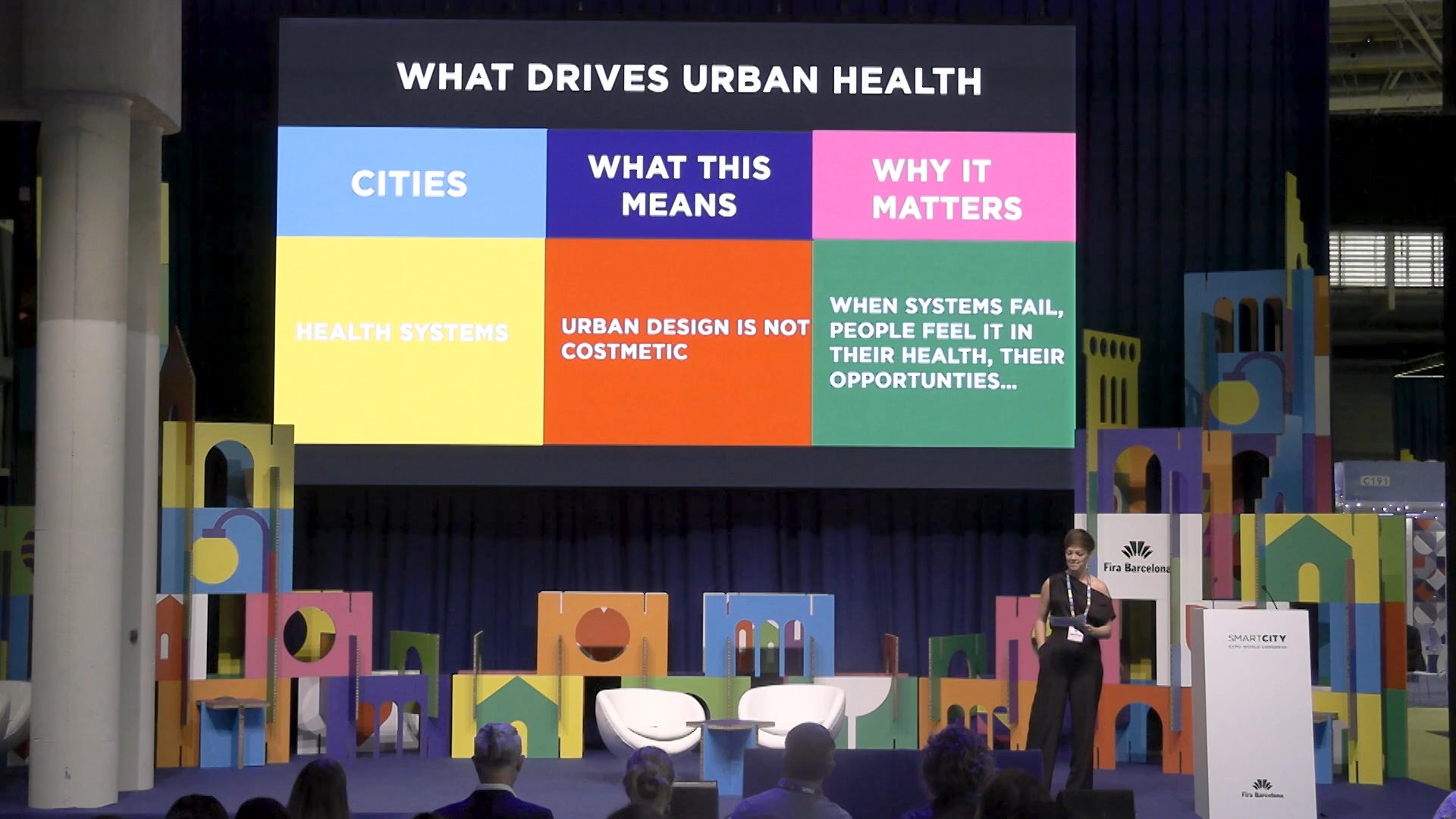

Favelas are shanty towns in Brazil. Many people in these places have basic-salary jobs and, therefore, low incomes. These jobs tend to have irregular shifts and various work locations. This makes it even more difficult to collect accurate data to help with town-planning.The problem with these slums is that their urban housing conditions tend to be so hard that they are declared “intolerable” by the United Nations itself. Insecurity, lack of basic services (particularly water and sewage), inadequate and unsafe construction structures, overcrowding, location in dangerous areas and high concentrations of poverty, as well as social and economic deprivation, broken families, unemployment, economic, physical and social exclusion are just some of the characteristics of these shanty towns.This, in turn, results in the inhabitants of these areas having limited access to credit and to the formal job market due to stigmatisation, discrimination and geographic isolation. Their inhabitants are more likely to suffer water-related diseases such as typhus and cholera and HIV/AIDS.

Remodelling instead of demolishing

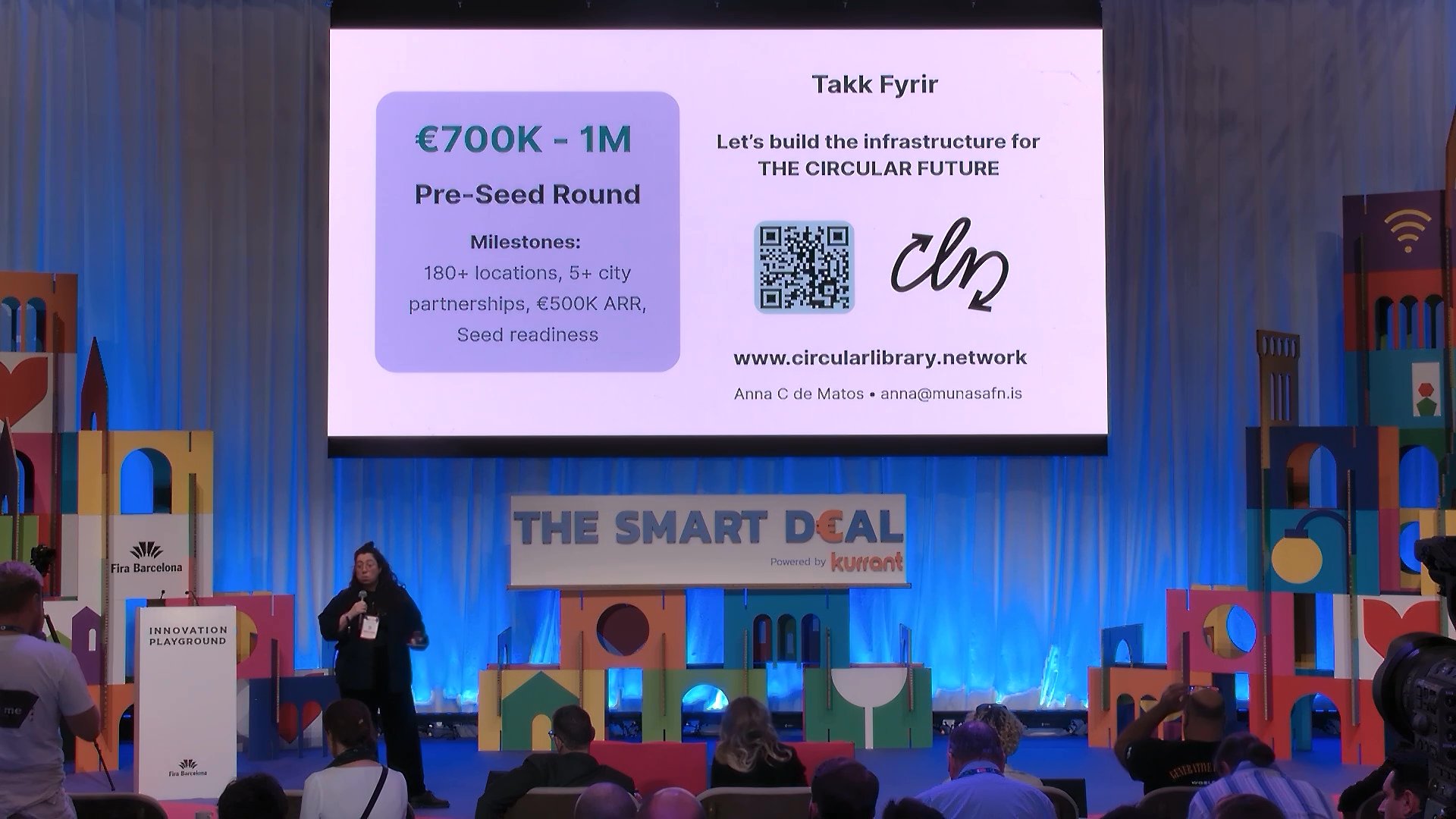

As a result of these circumstances, numerous governments decided to demolish these neighbourhoods as a way of eradicating all the problems associated with them. However, in 1980, Brazil decided to improve the quality of life in these shanty towns instead of demolishing them. The idea is that it is not just more humane to integrate the shanty towns into cities’ activities, but it would also be more economically beneficial than excluding them.Paraisópolis was one of the first places to try out this new strategy. One of São Paulo’s objectives is to take electricity sewage systems and drinking water to as many areas as possible. Furthermore, they are promoting a kind of “home exchange” programme: when a family abandons a shack to go to an apartment built by the government, a new family from a worse area can move into that shack until a better solution can be found.https://www.instagram.com/p/Bpo7fkolwoq/?utm_source=ig_web_button_share_sheetThe experience gained also enabled a national “City statute” to be established in 2001, which establishes that cities must have master plans in place for these shanty towns. This document also outlines a series of tools that can be used by municipalities, such as allowing cities to create “areas of special interest” for disorganised shanty towns, formally recognising them and classifying them for social services.

An alliance of cities

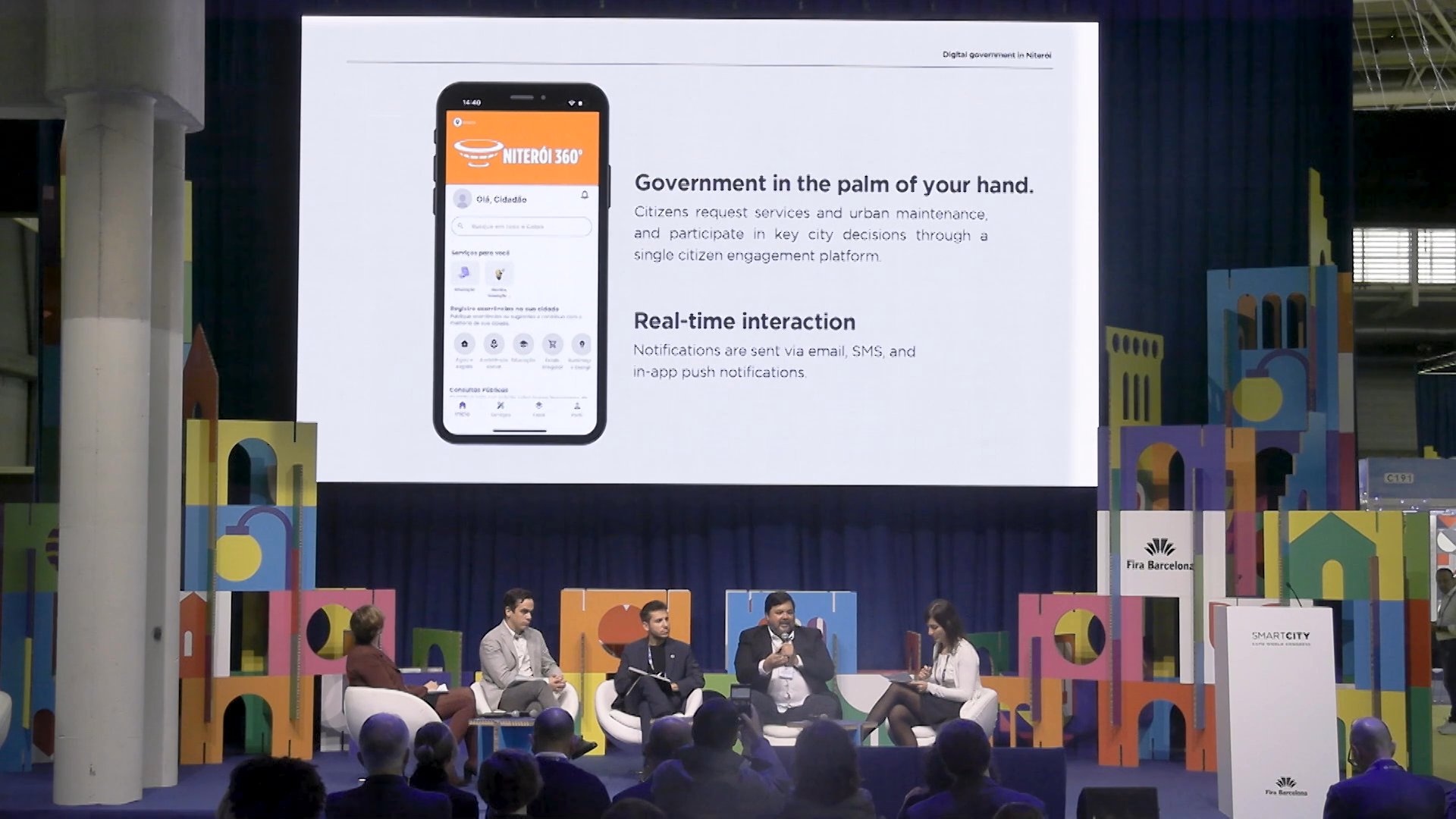

This City Statute is supported by Cities Alliance, a global partnership made up of national and local governments, UN-habitat and the World Bank, focused on extending solutions to combat urban poverty. One of the first measures is to always guarantee that settlements have access to running water and sewage services.In 2006, the city of São Paulo also introduced an information system which enables it to know the condition of the shanty towns or areas in danger of flooding, so the cleaning and maintenance services in the city can be managed more efficiently.

The figures corroborate the change

The changes and transformation of Paraisópolis are clear and measurable with actual figures. For example, between 2000 and 2010, the employment rate among those aged 18 or over increased from 65.61% to 66.24%. At the same time, the unemployment rate went from 10.86% in 2000 to 5.60% in 2010.Another indicator of this improvement is life expectancy at birth, one of the figures from Municipal Human Development Index (MHDI). In Paraisópolis , life expectancy at birth increased by 3.3 years over the last decade, going from 72.9 years in 2000 to 76.1 years in 2010. In 1991 it was 69.6 years. While the infant mortality rate (in children under the age of 1 year) dropped from 20.7 per thousand live births in 2000 to 13.7 per thousand live births in 2010. In 1991, the rate was 25.2.Paraisópolis , therefore, proves that certain measures can be applied in the most adverse conditions to improve the lives of the inhabitants and for those responsible in the city to have more facilities available in order to manage these deprived areas more efficiently.Images | nakagawaPROOF/Flickr, Wikimedia, Pixabay