This is a guest post by EIT Urban Mobility written by Victoria Campbell. EIT Urban Mobility is the leading innovation community for urban mobility in Europe, committed to accelerating the transition to sustainable mobility and more liveable urban spaces.

Europe is entering a demographic transformation. As of early 2024, over 20% of the European Union (EU) population is aged 65 or older —adding up to a population of roughly 90 million people. The population of older adults in Europe has been increasing in recent years as the generation of baby boomers has aged, with the share rising by almost three percentage points in the past decade alone. Meanwhile, those aged 80 or over have gone from about 3.8% in 2004 to over 6% in 2024. Projections suggest that by 2060, more than 30% of the EU’s population could be over 65.

An ageing Europe has wide-ranging implications not only for pensions, healthcare and labour markets but also for the structure of our cities. As elderly populations increase in our cities, how people move, how safe and comfortable public space is, and what infrastructure is available must adapt to serve their needs. To build liveable, inclusive cities for all, planners must consider: what do older people need, what are their unique mobility demands, and how can urban mobility systems evolve for the betterment of their lives as well as others?

The unique mobility needs of an ageing population

With advancing age come changes that affect mobility in both obvious and subtle ways. Studies have shown that as our bodies age we lose anywhere from 3-8% of muscle mass per decade after the age of 30 –resulting in diminished strength, slower walking speeds, reduced balance and decreased endurance. Therefore, climbing stairs or steep inclines, walking long distances, or quickly stepping in and out of raised vehicles like buses can become not only difficult but unsafe or impossible.

Sensory and cognitive changes further complicate mobility. Hearing, sight and reaction times decline, which makes it harder to navigate complex streets, read small signs or maps, discern audio announcements, or cope with busy intersections. Mild cognitive impairment becomes more common and can affect route choice, awareness and overall safety. In Spain, data from 2021 revealed that in urban areas, 64% of pedestrians killed on urban roads were people aged 65 and older, despite this group representing only about 20% of the population.

Older adults are also more vulnerable to environmental stresses. Heat waves, poor air quality, and the absence of shade or rest areas disproportionately affect them. In Madrid, for instance, research shows that extreme heat reduces walking among older adults, altering both their routes and their schedules.

Changing for the better

To address these challenges, cities must reimagine mobility through a lens of accessibility by default. Public transport systems that prioritise low-floor buses and trams, step-free boarding and lifts at all stations make daily journeys possible for vulnerable users. Large-print signage, high-contrast design and both audio and visual announcements allow people with visual or audio impairments to travel more confidently. Smooth, well-maintained sidewalks and properly designed curb cuts minimise risks of falls and create a more navigable public realm for mobility assistance-users.

Climate-oriented design is essential as our cities continue to experience more and more extreme heat. Providing more shade-covered seating along walking routes benefits older people by providing protection from the sun and opportunities for rest on journeys that might otherwise be long or daunting. Public drinking fountains can also offer respite on punishingly hot days.

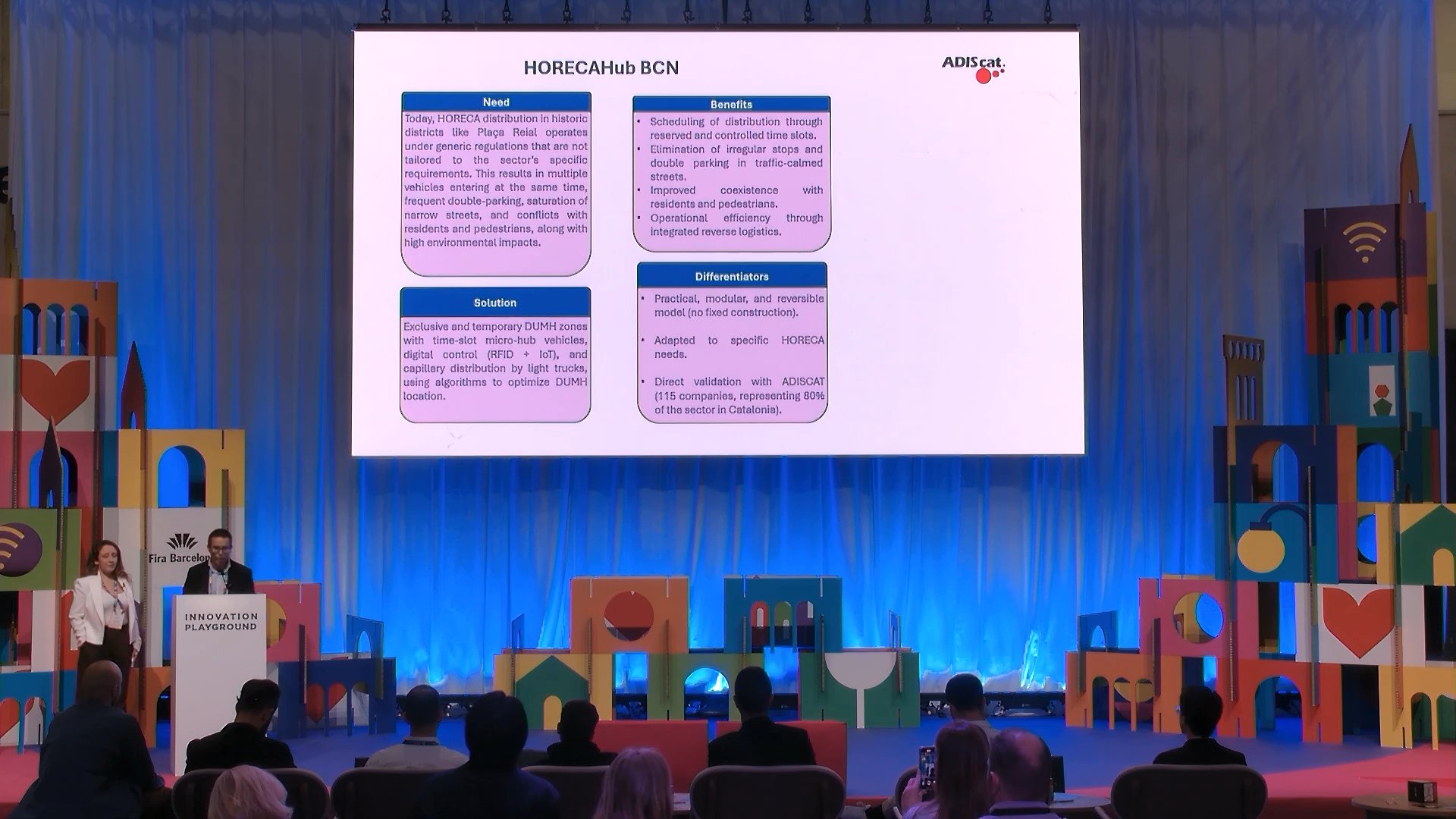

Within neighbourhoods, the 15-minute city design benefits all users, but especially older populations. If services such as shops, healthcare facilities and places for socialising are located closer to where people live, the need for longer or complicated journeys diminishes.

Prioritising the needs of pedestrians by reducing or eliminating private car traffic allows for better pedestrian connectivity and reduced opportunities for accidents and safety issues. Safety can be further enhanced through easy-to-implement infrastructure like audible crossing signals and extended crossing times to give older pedestrians more time to navigate traffic. In areas with reduced private car traffic, flexible transport options like demand-responsive shuttles and subsidised taxi services, can fill gaps for those who cannot rely solely on walking or standard public transport.

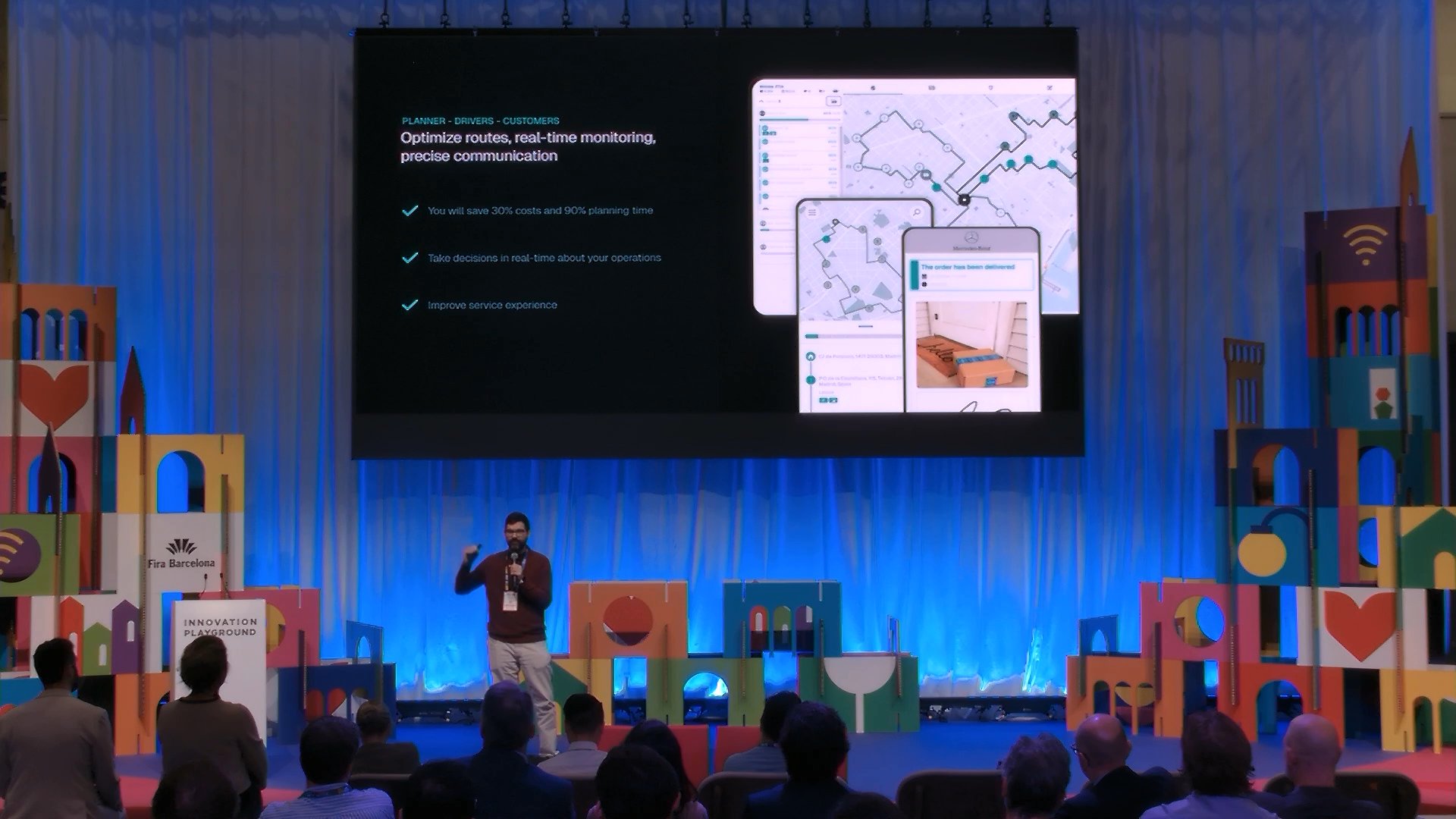

Digital tools also offer new possibilities but come with their own challenges. Route planners that highlight accessible paths, apps that display the location of elevators or public toilets and real-time updates about service disruptions can support the needs of older residents. But these tools must be designed accessibly and upskilling or training opportunities should be available to assist older populations with digital literacy.

Policies, examples and frameworks

Several European initiatives already point the way forward. The European Commission has made access to transport for all a political priority, noting that mobility is an essential service. The European Accessibility Act reinforces this by requiring that many products and services, including those related to mobility, be designed to accommodate users of all abilities.

At a local level, the New European Bauhaus’ ELDERS project worked with older residents in Masquefa, Spain, to co-design walking routes that reduce isolation and promote active mobility. In partnership with the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia, the initiative improved accessibility and public spaces while fostering social connection, offering a model other cities can replicate to build more inclusive environments.

Similarly, the EU-funded URBANAGE project has involved older residents directly in the design of age-friendly planning tools, while the Green Silver Age Mobility project in the Baltic Sea region has engaged seniors to better understand barriers to more sustainable mobility modes such as bike-sharing.

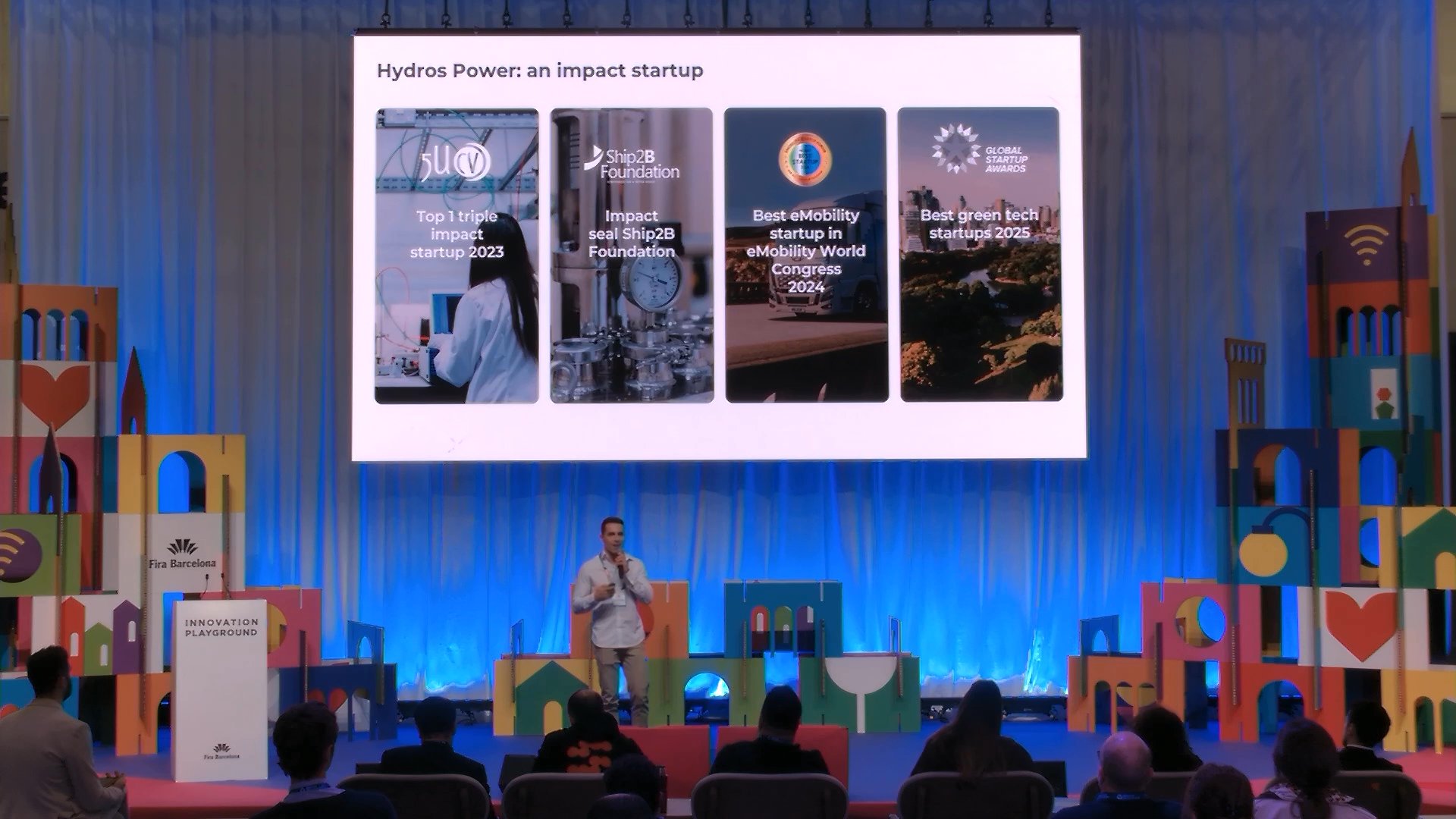

Startups too are innovating for impact. Dreamwaves, an Austrian startup, is rethinking mobility for blind and visually impaired people with its waveOut app. Supported by EIT Urban Mobility, the startup uses 3D sound navigation and computer vision to offer centimetre-level accuracy without costly infrastructure, guiding users through auditory “breadcrumbs.” As ocular function declines with age, Dreamwaves’ innovation helps older people keep their independence even if impacted by visual changes.

Inclusive design benefits all

Although these infrastructural and digital changes respond directly to the needs of older populations, the benefits extend across all user groups. Parents pushing strollers, tourists with luggage and people recovering from injuries all find ramps, low steps and smoother sidewalks just as useful. Much of the changes made for our oldest residents tend to also benefit our youngest. Child-friendly design also prioritises safer crossings, shorter wait times at traffic lights and better signage. Additionally, families enjoy the presence of public seating, water fountains, shade and green spaces.

As with Dreamwaves’ innovation —visual wayfinding, improved signage and tactile paving support not only older adults but also those with visual impairments.

The advantages of accessible and universal design are not limited to individuals. Cities with walkable neighbourhoods, accessible public spaces and inclusive transport networks often see stronger local economies, higher property values and more vibrant street life. More walkable cities also encourage physical activity, reduce social isolation and improve public health. Positive environmental impacts are also significant: incentivising walking and public transport and disincentivising car use, cuts both congestion and emissions. In short, designing for older people catalyses improvements that benefit everyone.

If European cities are to remain liveable, socially just and sustainable as our populations increase in age, significant strides must be made for true accessibility. Public transport, sidewalks, streets and public spaces must be designed to serve people from early childhood through advanced age. The benefits of doing so extend beyond single user groups to create safer, healthier and more inclusive urban environments for all.

Photos: EIT Urban Mobility, Foto de Rollz International en Unsplash